Link to AUGUSTINE1 CONSERVATIVE CHRISTIAN WORLDVIEW BLOG

Nehemiah John MacArthur *

Title

Nehemiah (“Jehovah comforts”) is a famous cupbearer, who never appears in Scripture outside of this book. As with the books of Ezra and Esther, named after his contemporaries (see Introductions to Ezra and Esther), the book recounts selected events of his leadership and was titled after him. Both the Greek Septuagint (LXX) and the Latin Vulgate named this book “Second Ezra.” Even though the two books of Ezra and Nehemiah are separate in most English Bibles, they may have once been joined together in a single unit as currently in the Hebrew texts. New Testament writers do not quote Nehemiah.

Author and Date

Though much of this book was clearly drawn from Nehemiah’s personal diaries and written from his first person perspective (1:1–7:5; 12:27–43; 13:4–31), both Jewish and Christian traditions recognize Ezra as the author. This is based on external evidence that Ezra and Nehemiah were originally one book as reflected in the LXX and Vulgate; it is also based on internal evidence such as the recurrent “hand of the LORD” theme which dominates both Ezra and Nehemiah and the author’s role as a priest-scribe. As a scribe, he had access to the royal archives of Persia, which accounts for the myriad of administrative documents found recorded in the two books, especially in the book of Ezra. Very few people would have been allowed access to the royal archives of the Persian Empire, but Ezra proved to be the exception (cf. Ezra 1:2–4; 4:9–22; 5:7–17; 6:3–12).

The events in Nehemiah 1 commence late in the year 446 B.C., the 20th year of the Persian king, Artaxerxes (464–423 B.C.). The book follows chronologically from Nehemiah’s first term as governor of Jerusalem ca. 445–433 B.C. (Neh. 1–12) to his second term, possibly beginning ca. 424 B.C. (Neh. 13). Nehemiah was written by Ezra sometime during or after Nehemiah’s second term, but no later than 400 B.C.

Background and Setting

True to God’s promise of judgment, He brought the Assyrians and Babylonians to deliver His chastisement upon wayward Judah and Israel. In 722 B.C. the Assyrians deported the 10 northern tribes and scattered them all over the then known world (2 Kin. 17). Several centuries later, ca. 605–586 B.C., God used the Babylonians to sack, destroy, and nearly depopulate Jerusalem (2 Kin. 25) because Judah had persisted in her unfaithfulness to the covenant. God chastened His people with 70 years of captivity in Babylon (Jer. 25:11).

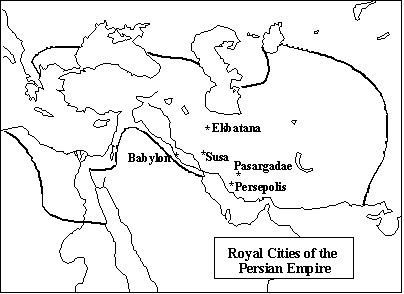

During the Jews’ captivity, world empire leadership changed hands from the Babylonians to the Persians (ca. 539 B.C.; Dan. 5), after which Daniel received most of his prophetic revelation (cf. Dan. 6, 9–12). The book of Ezra begins with the decree of Cyrus, a Persian king, to return God’s people to Jerusalem to rebuild God’s house (ca. 539 B.C.), and chronicles the reestablishment of Judah’s national calendar of feasts and sacrifices. Zerubbabel and Joshua led the first return (Ezra 1–6) and rebuilt the temple. Esther gives a glimpse of the Jews left in Persia (ca. 483–473 B.C.) when Haman attempted to eliminate the Jewish race. Ezra 7–10 recounts the second return led by Ezra in 458 B.C. Nehemiah chronicles the third return to rebuild the wall around Jerusalem (ca. 445 B.C.).

At that time in Judah’s history, the Persian Empire dominated the entire Near Eastern world. Its administration of Judah, although done with a loose hand, was mindful of disruptions or any signs of rebellion from its vassals. Rebuilding the walls of conquered cities posed the most glaring threat to the Persian central administration. Only a close confidant of the king himself could be trusted for such an operation. At the most critical juncture in Judah’s revitalization, God raised up Nehemiah to exercise one of the most trusted roles in the empire, the King’s cupbearer and confidant. Life under the Persian king Artaxerxes (ca. 464–423 B.C.) had its advantages for Nehemiah. Much like Joseph, Esther, and Daniel, he had attained a significant role in the palace which then ruled the ancient world, a position from which God could use him to lead the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s walls in spite of its implications for Persian control of that city.

Several other historical notes are of interest. First, Esther was Artaxerxes’ stepmother and could have easily influenced him to look favorably upon the Jews, especially Nehemiah. Second, Daniel’s prophetic 70 weeks began with the decree to rebuild the city issued by Artaxerxes in 445 B.C. (cf. chaps. 1, 2). Third, the Elephantine papyri (Egyptian documents), dated to the late 5th century B.C., support the account of Nehemiah by mentioning Sanballat the governor of Samaria (2:19), Jehohanan (6:18; 12:23), and Nehemiah’s being replaced as governor of Jerusalem by Bigvai (ca. 410 B.C; Neh. 10:16). Finally, Nehemiah and Malachi represent the last of the OT canonical writings, both in terms of the time the events occurred (Mal. 1–4; Neh. 13) and the time when they were recorded by Ezra. Thus the next messages from God for Israel do not come until over 400 years of silence had passed, after which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus Christ were announced (Matt. 1; Luke 1, 2).

With the full OT revelation of Israel’s history prior to Christ’s incarnation being completed, the Jews had not yet experienced the fullness of God’s various covenants and promises to them. While there was a Jewish remnant, as promised to Abraham (cf. Gen. 15:5), it does not appear to be even as large as at the time of the Exodus (Num. 1:46). The Jews neither possessed the Land (Gen. 15:7) nor did they rule as a sovereign nation (Gen. 12:2). The Davidic throne was unoccupied (cf. 2 Sam. 7:16), although the High-Priest was of the line of Eleazar and Phinehas (cf. Num. 25:10–13). God’s promise to consummate the New Covenant of redemption awaited the birth, crucifixion, and resurrection of Messiah (cf. Heb. 7–10).

Historical and Theological Themes

Careful attention to the reading of God’s Word in order to perform His will is a constant theme. The spiritual revival came in response to Ezra’s reading of “the Book of the Law of Moses” (8:1). After the reading, Ezra and some of the priests carefully explained its meaning to the people in attendance (8:8). The next day, Ezra met with some of the fathers of the households, the priests, and Levites, “in order to understand the words of the Law” (8:13). The sacrificial system was carried on with careful attention to perform it “as it is written in the Law” (10:34, 36). So deep was their concern to abide by God’s revealed will that they took “a curse and an oath to walk in God’s Law … ” (10:29). When the marriage reforms were carried out, they acted in accordance with that which “they read from the Book of Moses” (13:1).

A second major theme, the obedience of Nehemiah, is explicitly referred to throughout the book due to the fact that the book is based on the memoirs or first person accounts of Nehemiah. God worked through the obedience of Nehemiah; however, He also worked through the wrongly-motivated, wicked hearts of His enemies. Nehemiah’s enemies failed, not so much as a result of the success of Nehemiah’s strategies, but because “God had brought their plot to nothing” (4:15). God used the opposition of Judah’s enemies to drive His people to their knees in the same way that He used the favor of Cyrus to return His people to the Land, to fund their building project, and to even protect the reconstruction of Jerusalem’s walls. Not surprisingly, Nehemiah acknowledged the true motive of his strategy to repopulate

Jerusalem: “my God put it into my heart” (7:5). It was He who accomplished it.

Jerusalem: “my God put it into my heart” (7:5). It was He who accomplished it.

Another theme in Nehemiah, as in Ezra, is opposition. Judah’s enemies started rumors that God’s people had revolted against Persia. The goal was to intimidate Judah into forestalling reconstruction of the walls. In spite of opposition from without and heartbreaking corruption and dissension from within, Judah completed the walls of Jerusalem in only 52 days (6:15), experienced revival after the reading of the law by Ezra (8:1ff.), and celebrated the Feast of Tabernacles (8:14ff.; ca. 445 B.C.).

The book’s detailed insight into the personal thoughts, motives, and disappointments of Nehemiah makes it easy for the reader to primarily identify with him, rather than “the sovereign hand of God” theme and the primary message of His control and intervention into the affairs of His people and their enemies. But the exemplary behavior of the famous cupbearer is eclipsed by God who orchestrated the reconstruction of the walls in spite of much opposition and many setbacks; the “good hand of God” theme carries through the book of Nehemiah (1:10; 2:8, 18).

Interpretive Challenges

First, since much of Nehemiah is explained in relationship to Jerusalem’s gates (cf. Neh. 2, 3, 8, 12), one needs to see the map “Jerusalem in Nehemiah’s Day” for an orientation. Second, the reader must recognize that the time line of chapters 1–12 encompassed about one year (445 B.C.), followed by a long gap of time (over 20 years) after Neh. 12 and before Neh. 13. Finally, it must be recognized that Nehemiah actually served two governorships in Jerusalem, the first from 445–433 B.C. (cf. Neh. 5:14; 13:6) and the second beginning possibly in 424 B.C. and extending to no longer than 410 B.C.

Outline

I. Nehemiah’s First Term as Governor (1:1–12:47)

A. Nehemiah’s Return and Reconstruction (1:1–7:73a)

1. Nehemiah goes to Jerusalem (1:1–2:20)

2. Nehemiah and the people rebuild the walls (3:1–7:3)

3. Nehemiah recalls the first return under Zerubbabel (7:4–73a)

B. Ezra’s Revival and Renewal (7:73b–10:39)

1. Ezra expounds the law (7:73b–8:12)

2. The people worship and repent (8:13–9:37)

3. Ezra and the priests renew the covenant (9:38–10:39)

C. Nehemiah’s Resettlement and Rejoicing (11:1–12:47)

1. Jerusalem is resettled (11:1–12:26)

2. The people dedicate the walls (12:27–47)

II. Nehemiah’s Second Term as Governor (13:1–31)

Nehemiah’s Historical Background *

The Jews faced complete destruction of their own possessions, traditions, the temple and their country. They had sinned and God had judged them (1-2 Kings, 1-2 Chronicles along with most of the prophets). Significant dates are below.

Jerusalem destroyed and temple burned on July 18, 586 B.C. (2 Kings 24).

Oct 29, 539 B.C., Babylon fell to Medes and Persians.

God, however, promised to remake Israel. This is the way the Lord rebuilt Jerusalem. Emperor Cyrus’ in his first year of ruling the Persian empire, he issued a decree allowing Jews to return to their land – seventy years later as prophesied. They made three returns:

Ancient Jerusalem after the wall is rebuilt

1) Zerubbabel led the first wave of Jewish exiles to return in 536 B.C. (Ezra 1-6)

- (Big gap of 57 years – Esther’s time)

- In 535 B.C. the construction of the temple began.

- In Feb 18, 516 B.C. the temple was completed and dedicated.

2) Ezra led the second in 455 B.C. (Ezra 7-10)

- Ezra left with about 1500 men and their families in mid-March 455 B.C.

- In August of 455 B.C., the little group arrives safely in Jerusalem.

3) Nehemiah led the third in 445 B.C. (Neh 1-3)

- In Dec. of 446 B.C., Nehemiah hears of the report.

- In April of 445 B.C., after a prayer period of four months, Nehemiah speaks with the king

- Early September, after just 52 days, the wall was completed.

Introduction Notes on Nehemiah Dr. Thomas L. Constable

Title

This book, like so many others in the Old Testament, received its title from its principal character. The Septuagint (Greek) translation also had the same title, as does the Hebrew Bible. The Jews kept Ezra and Nehemiah together for many years. The reason was the historical continuity that flows from Ezra through Nehemiah.

Writer and Date

The use of the first person identifies the author as Nehemiah, the governor of the Persian province of Judah (1:1—2:20; 13:4-31). His name means “Yahweh has comforted” or “Yahweh comforts.”

The mention of Darius the Persian in 12:22 probably refers to Darius II, the successor of Artaxerxes I (Longimanus).

Darius ruled from 423-404 B.C. The text refers to an event that took place in Darius’ reign (12:22). Therefore Nehemiah must have written the book sometime after that reign began. Since there are no references to Nehemiah’s age in the text, it is hard to estimate how long he may have lived. When the book opens, he was second in command under King Artaxerxes (cf. Daniel). If he was 40 years old then and 41 when he reached Jerusalem in 444 B.C., he would have been 62 years old in 423 B.C. when Darius replaced Artaxerxes. Consequently he probably wrote the book not long after 423 B.C., most likely before 400 B.C.

Scope

The years of history the book covers are 445-431 B.C., or perhaps a few years after that. In 445 B.C. (the twentieth year of Artaxerxes’ reign, 1:1) Nehemiah learned of the conditions in Jerusalem that led him to request permission to return to Judah (2:5). He arrived in Jerusalem in 444 B.C. and within 52 days had completed the rebuilding of the city walls (6:15). In 432 B.C. Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes (13:6). He came back to Jerusalem after that, probably in a year or so. The record of his reforms following that return is in the last chapter of this book. Apparently Nehemiah completed all of them in just a few weeks or months. Even though the book spans about 15 years, most of the activity Nehemiah recorded took place in 445-444 B.C. (chs. 1—12) and in 432-431 B.C. (ch. 13).

Chronology of the Book of Nehemiah

| |

445

|

Nehemiah learned of conditions in Jerusalem and requested a leave of absence from Artaxerxes.

|

444

|

He led the Jews to Jerusalem. Repairs on the wall of Jerusalem began. The Jews completed rebuilding the walls. Nehemiah promoted spiritual renewal among the returnees.

|

432

|

Nehemiah returned to Artaxerxes ending his 12 years as governor of Judah. Malachi may have prophesied in Jerusalem.

|

431

|

Nehemiah may have returned to Jerusalem and began his second term as governor. More religious reforms apparently began.

|

Historicity

“The historicity of the book has been well established by the discovery of the Elephantine papyri, which mention Johanan (12:22, 23) as high priest in Jerusalem, and the sons of Sanballat (Nehemiah’s great enemy) as governors of Samaria in 408 B.C. We also learn from these papyri that Nehemiah had ceased to be the governor of Judea before that year, for Bagoas is mentioned as holding that position.”

The Elephantine papyri are letters the Jews in Babylon sent to Jews who had fled to a colony in southern Egypt called Elephantine following the destruction of Jerusalem. They throw much light on Jewish life as it existed in Babylon during the exile.

Outline

I. The fortification of Jerusalem chs. 1—7

A. The return under Nehemiah chs. 1—2

1. The news concerning Jerusalem 1:1-3

2. The response of Nehemiah 1:4-11

3. The request of Nehemiah 2:1-8

4. The return to Jerusalem 2:9-20

B. The rebuilding of the walls 3:1—7:4

1. The workers and their work ch. 3

2. The opposition to the workers ch. 4

3. The strife among the workers ch. 5

4. The attacks against Nehemiah 6:1-14

5. The completion of the work 6:15—7:4

C. The record of those who returned 7:5-72

II. The restoration of the Jews chs. 8—13

A. The renewal of the Mosaic Covenant chs. 8—10

1. The gathering of the people ch. 8

2. The prayer of the people ch. 9

3. The renewed commitment of the people ch. 10

B. The residents of the land 11:1—12:26

1. The residents of Jerusalem 11:1-24

2. The residents of the outlying towns 11:25-36

3. The priests and Levites 12:1-26

C. The dedication of the wall 12:27-47

1. Preparations for the dedication 12:27-30

2. The dedication ceremonies 12:31-47

D. The reforms instituted by Nehemiah ch. 13

1. The exclusion of foreigners 13:1-3

2. The expulsion of Tobiah 13:4-9

3. The revival of tithing 13:10-14

4. The observance of the Sabbath 13:15-22

5. The rebuke of mixed marriages 13:23-29

6. The summary of Nehemiah’s reforms 13:30-31

Exposition

I. The Fortification Of Jerusalem chs. 1—7

“The first seven chapters of Nehemiah as well as 12:31—13:31 are written in the first person. This, as well as all or part of Neh 11 and the rest of Neh 12, constitutes what is called the Nehemiah Memoirs. As such it offers an extensive look into the life and heart of an outstanding servant of God that is unique to the Old Testament.”

A. The Return under Nehemiah chs. 1—2

The focus of restoration activities in Nehemiah is on the walls of Jerusalem. In Ezra it was the altar of burnt offerings and especially the temple in Jerusalem.

“The orientation of Nehemiah is more civil and secular than that of Ezra, but it is also written from the priestly point of view.”

The walls of the city had lain in ruins since 586 B.C. At that time Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, breached them, entered Jerusalem, burned the temple, carried most of the remaining Jews off to Babylon, and kno cked the walls down. Consequently the few Jews who remained could not defend themselves (2 Kings 25:1-11). The returned exiles had attempted to rebuild the walls in or shortly after 458 B.C., but that project failed because of local opposition (Ezra 4:12, 23).

cked the walls down. Consequently the few Jews who remained could not defend themselves (2 Kings 25:1-11). The returned exiles had attempted to rebuild the walls in or shortly after 458 B.C., but that project failed because of local opposition (Ezra 4:12, 23).

cked the walls down. Consequently the few Jews who remained could not defend themselves (2 Kings 25:1-11). The returned exiles had attempted to rebuild the walls in or shortly after 458 B.C., but that project failed because of local opposition (Ezra 4:12, 23).

cked the walls down. Consequently the few Jews who remained could not defend themselves (2 Kings 25:1-11). The returned exiles had attempted to rebuild the walls in or shortly after 458 B.C., but that project failed because of local opposition (Ezra 4:12, 23).

The returned exiles had received permission to return to their land and to reestablish their unique national institutions as much as possible. Therefore they needed to rebuild the city walls to defend themselves against anyone who might want to interfere with and to interrupt their way of life.

1. The news concerning Jerusalem 1:1-3

The month Chislev (v. 1) corresponds to our late November and early December. The year in view was the twentieth year of Artaxerxes’ reign (i.e., 445-444 B.C.). Susa (or Shushan, in Hebrew) was a winter capital of Artaxerxes (cf. Esth. 1:2). The main Persian capital at this time was Persepolis.

Hanani (v. 2) seems to have been Nehemiah’s blood brother (cf. 7:2). The escape in view refers to the Jews’ escape back to Judea from captivity in Babylon. Even though they received official permission to return, Nehemiah seems to have regarded their departure from Babylon as an escape since the Babylonians had originally forced them into exile against their wills.

The news that Nehemiah received evidently informed him of the Jews’ unsuccessful attempts to rebuild Jerusalem’s walls in 458 B.C. (Ezra 4:23-24).

“It was an ominous development, for the ring of hostile neighbors round Jerusalem could now claim royal backing. The patronage which Ezra had enjoyed (cf. Ezra 7:21-26) was suddenly in ruins, as completely as the city walls and gates. Jerusalem was not only disarmed but on its own.”

2. The response of Nehemiah 1:4-11

Nehemiah’s reaction to this bad news was admirable. He made it a subject of serious prolonged prayer (vv. 4, 11; 2:1). Daniel had been another high-ranking Jewish official in the Persian government, and he too was a man of prayer.

“Of the 406 verses in the book, the prayers fill 46 verses (11%), and the history accounts for 146 (36%). The various lists . . . add up to 214 verses or 53% of the total.”

Nehemiah began his prayer with praise for God’s greatness and His loyal love for His people (v. 5). As Ezra had done, he acknowledged that the Jews had been guilty of sinning against God (cf. Ezra 9:6-7). They had disobeyed the Mosaic Law (v. 7). Nehemiah reminded God of His promise to restore His people to their land if they repented (vv. 8-9; cf. Deut. 30:1-5). He also noted that these were the people Yahweh had redeemed from Egyptian slavery for a special purpose (v. 10; cf. Deut. 9:29). He concluded with a petition that his planned appeal to the king would be successful (v. 11a).

“With the expression this man at the end of the prayer Nehemiah shows the big difference between his reverence for his God and his conception of his master, the Persian king. In the eyes of the world Artaxerxes was an important person, a man with influence, who could decide on life or death. In the eyes of Nehemiah, with his religious approach, Artaxerxes was just a man like any other man. The Lord of history makes the decisions, not Artaxerxes.”

“Although he is a layperson, he stands with the great prophets in interceding for his people and in calling them to be faithful to the Sinai covenant.”

If Nehemiah wrote this book, he was also a prophet (cf. Daniel). Extrabiblical references that mention the office of cupbearer in the Persian court have revealed that this was a position second only in authority to the king (v. 11b). Nehemiah was not only the chief treasurer and keeper of the king’s signet ring, but he also tasted the king’s food to make sure no one had poisoned it (Tobit 1:22).

“The cupbearer . . . in later Achaemenid times was to exercise even more influence than the commander-in-chief.”

“Achaememid” refers to the dynasty of Persian rulers at this time.

“From varied sources it may be assumed that Nehemiah as a royal cupbearer would probably have had the following traits: 1. He would have been well trained in court etiquette (cf. Dan. 1:4-5). 2. He was probably a handsome individual (cf. Dan. 1:4, 13, 15). 3. He would certainly know how to select the wines to set before the king. . . . 4. He would have to be a convivial companion to the king with a willingness to lend an ear at all times. . . . 5. He would be a man of great influence as one with the closest access to the king, and one who could well determine who could see the king. 6. Above all, Nehemiah had to be an individual who enjoyed the unreserved confidence of the king.”

Some commentators have concluded that Nehemiah as cupbearer must have been a eunuch. This opinion rests on the translation of the Greek wordeunouchos (“eunuch”) instead of oinochoos (“cupbearer”) in one version of the Septuagint. However this rendering appears to have been an error in translation since the Hebrew word means cupbearer.

“Like many since his time, Nehemiah’s greatness came from asking great things of a great God and attempting great things in reliance on him.”

*****************************************************************************************************************************************************

* Available online at: http://www.gty.org/resources/bible-introductions/MSB16

COPYRIGHT ©2015 Grace to You We are happy to allow you permission to use content from the Resources section of our website under the following guidelines. Using GTY Web Content – General Guidelines

- Provide the content for free.

- Make no changes to the content.

- Credit the content to John MacArthur or Grace to You.

- Cite the copyright information (e.g. Copyright 2007, Grace to You. All rights reserved. Used by permission.).

- Cite the source by providing the Web address (www.gty.org).

The above post may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. It is being made available in an effort to advance the understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, social justice, for the purpose of historical debate, and to advance the understanding of Christian conservative issues. It is believed thatthis constitutes a ”fair use” of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the Copyright Law. In accordance with the title 17 U.S. C. section 107, the material in this post is shown without profit to those who have expressed an interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.

Federal law allows citizens to reproduce, distribute and exhibit portions of copyrighted motion pictures, video taped or video discs, without authorization of the copyright holder. This infringement of copyright is called “Fair Use”, and is allowed for purposes ofcriticism, news, reporting, teaching, and parody. This articles is written, and any image and video (includes music used in the video) in this article are used, in compliance with this law: Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. 107.

Link to Net Bible

Link to Answers in Genesis Ministries

Link to CNS News